Insights interview: the promise and practicalities of next-generation K-12 digital assessment

What’s the purpose of this interview and who’s it for?

What is the promise of next-generation K-12 digital assessment for better teaching and learning? And, what are the opportunities and practical considerations for innovative edtechs?

The pivot of K-12 education from face to face and blended to fully online through COVID-19 revealed some surprising benefits. Everyone is talking about how data will transform teaching and personalize learning. And, investment in promising new edtech companies who aim to disrupt entrenched competitors is at an all-time high (2020 was a record year for investment in US edtech and globally).

But all these opportunities rest on the promise and practicalities of K-12 digital assessment. In particular, the value and reliability of data-driven insights into a learner’s progress (their knowledge, skills, and ability to apply both) are only as good as the underlying assessments and data captured. And, many traditional assessments don’t translate well into a digital environment—let alone exploit what digital can uniquely enable.

So, if we step back, what is the promise of next-generation K-12 digital assessment? And, how can edtech leaders ensure they’re building the right thinking, talent, and capabilities into their product and business?

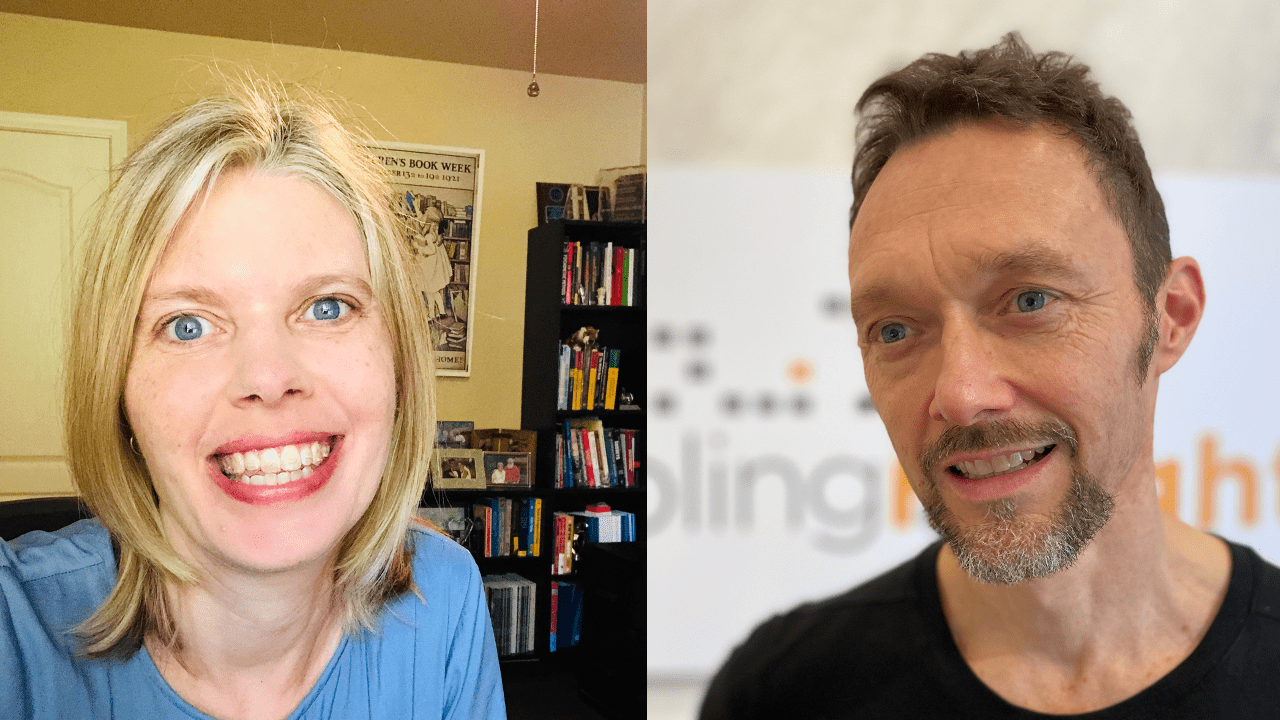

Insights from Kristen DiCerbo

Given the foundational importance of digital assessment, and my experiences of finding that many edtechs haven’t designed digital assessments optimally or instrumented the right data capture, I thought it would be valuable to tap someone who I’ve admired for many years as a leading light in emerging K-12 assessment practices and technologies—Dr. Kristen DiCerbo. Kristen is currently the Chief Learning Officer of Khan Academy. She started off as a psychologist in elementary schools, has held a variety of Learning Research roles at Pearson and Cisco, and has authored many insightful research papers.

The interview

Good morning, Kristen! Thanks so much for making time for this interview. You know that I provide strategic consulting to edtech startups and mature education companies in their digital evolution. With that audience in mind, I’d love to pick your brain about the promises and practicalities of next-generation K-12 digital assessment. I admire the depth of your expertise here, so I hope you don’t mind me starting at the highest level of “why” and then drill down into the “how”. In particular, I’d like to explore six key areas with you:

1. What are the problems with today’s K-12 classroom assessment?

2. What are the opportunities for next-generation K-12 digital assessment?

3. What are the market opportunities and challenges that lie ahead?

4. How can next-generation digital assessment be more equitable?

5. What are common pitfalls to avoid when designing digital assessment?

6. What resources on digital assessment design would you recommend?

Do those goals sound good?

Yes, those sound like great topics to explore. Please ask away, Adam!

0. What’s assessment?

Let’s start with defining what we’re talking about. In your view, what is assessment and what is it not?

Assessment is taking things we can observe and using them to make inferences about a student’s knowledge, skills, or other attributes (e.g., persistence, motivation, etc.).

A key part of this definition is the inference about the learner. There are a lot of things we can do with data from online learning systems. For example, we can measure how long a student takes to do something and whether they get to a correct answer and, based on that, serve up a piece of feedback. In this example, we aren’t doing anything to create an explicit estimate of their knowledge or skill. We are moving from observation to action. That is a good thing to do! But it is not assessment. Assessment would be, in this example, taking that time and correctness information and updating an estimate of the student’s proficiency in a particular skill (which we could use to determine what to serve up next.) The behaviors we observe in our online systems provide evidence that we can use to help improve those estimates.

Traditional assessment involves creating specific opportunities to observe knowledge or skill that we call tests. We typically observe things like the option chosen on a multiple choice test or the words written in response to short-answer and essay prompts. Since we are able to observe much more about student performance in our online learning systems, we should be able to create much better estimates of what our learners know and can do, AND we can better use those estimates to tailor learner experiences.

1. Limitations of current K-12 assessment

What are the problems with today’s K-12 classroom assessment practices?

It is important to recognize that classroom assessment takes many forms, from a teacher noting who looks puzzled and bored in class to an end-of-the-year, government-mandated timed test of the standards to be learned in a given year. If you’re thinking assessment means a ten-question multiple choice quiz after learning, stop now and think more broadly about assessment as any way we gather evidence about what someone knows or can do.

Assessment serves multiple purposes that can largely be broken down into assessment of learning (aimed at discovering whether learners learned what we intended them to, usually summative assessment) and assessment for learning (aimed at discovering what learners know and can do so as to inform future instruction, usually formative assessment). In addition, there is classroom assessment directed by the teacher and then other assessments that may be district, state, or federally mandated. Most edtech companies are focusing on classroom assessments, so I’ll concentrate most of my thoughts there.

It is important to understand that many teachers believe they have the classroom assessment tools they need. If you are in the business of user-centered design focused on understanding teacher pain points, you may not hear much about assessment. Teachers have, for example, their own observations, “exit tickets” (quick problems students do at the end of class and hand in), homemade exams, and item banks from their textbook/curriculum providers. Most teachers will tell you they have a pretty good idea about what their students know and can do.

The one issue teachers will bring up is that testing takes up a lot of classroom time, and this reduces the time for teaching and learning. Some estimates suggest that if we were to eliminate testing we could add 20 to 40 minutes more instruction per school day. Teachers also lament the amount of time it takes to grade homework and tests, usually in the evening and weekend hours.

In addition, we learned from the past year’s mass move to online environments that moving a paper and pencil test online as-is creates problems. In online environments, there is no “clear off your desks and take out a pencil” equivalent that prevents students from using other resources to find answers to questions that ask for fact recall. So, we can either spend a lot of time figuring out ways to “stop cheating” and create what (to my mind) are fairly invasive proctoring systems or we can design assessment so the activity teachers request of their students is not so easily “gamed.” If online learning is here to stay, we need to think about assessment differently.

Finally, one of the biggest goals of learning is knowing when and how to apply newly learned knowledge to new contexts in combinations with other skills. Assessing this ability to transfer skills to new contexts is difficult with traditional assessment systems. When we do try to introduce context in traditional systems, it often turns into written scenarios that add additional reading burden that can mean we are actually testing reading skill rather than the knowledge and skills we were targeting.

Overall, this means that teachers are spending a lot of time testing their students without getting important information about which students are able to apply their skills across contexts.

2. The promise of next-generation K-12 digital assessment

What do you see as the promise of next-generation K-12 digital assessment for solving these problems?

A key feature of online digital products is their ability to capture and store large amounts of data. This should fundamentally change how we think about assessment because it means we don’t have to stop learning and say “wait, now we have to take a test to gather data about what you know.” Instead, we can gather data as students are engaged in their learning activity and use that to make inferences. Essentially, we can have assessment without tests.

On a traditional test we most often only get a student’s final response. We compare this to a key or rubric and get either a judgement of right/wrong or a score on a 1-5 rubric scale. Based on these kinds of assessments, in a digital environment, we can expect a report of activities completed, an estimate of time spent, and some kind of score or estimate of mastery. Here is an example of presenting that information in a clear and useful way from Think Through Math.

In a digital environment, we can also go much further and measure, for example, steps students take to solve a problem (whether that be steps in a math problem or a series of actions in a virtual lab), records of multiple attempts, and length of time it takes to arrive at a solution. We can also gather information such as how far in advance students begin an assignment from a due date and how much time they spend in an online system each week. With this information, we can make inferences about not only a student’s levels of achievement, but also potentially misconceptions they have, their study skills, and effort they are investing (which we might call engagement or motivation).

All of this can help us to more precisely estimate achievement, and also understand why students performed as they did (e.g., they have a misconception, they were rushing, they don’t have good study skills). This added information should then expand the universe of potential interventions we can also offer to learners.

Before we get too excited, remember we are still making inferences from observed behaviors. So, when we see a student spending 20 minutes on a problem, we could infer they are struggling, but maybe they also went to the kitchen to get a snack. We are getting more information than from a traditional assessment but we still are making inferences. We only have the data that is in our systems, so we are still missing a lot. So, we should always seek to be aware of the potential that our inferences are incorrect, and give learners and instructors choice in our systems, as they have more and different information than we do.

Another key capability of digital environments is the ability to simulate environments and draw learners into them. The most obvious application of simulations is in science where we can create simulations to either test things that are too dangerous for learners to test in real life or see things that aren’t visible to the naked eye. The Phet simulations have long been recognized as excellent teaching tools and more recently the team behind them has developed interoperable simulations called PhET-iO simulations that include streaming output data that opens up many new possibilities for using them for assessment too.

Inq-ITS is a company that provides virtual science labs and assessments in the K-12 and combines use of digital data and simulations. They simulate everything from plant cells to planets. Students respond to both open- and close-ended questions. The system uses their responses and data gathered from the system to respond with a virtual tutor (who can ask questions and prompt behaviors) and create teacher alerts (keeping the human in the loop!).

Can you share examples of how these formative insights can empower a teacher to better help students?

I have found three instructional decisions teachers are interested in using data to inform:

- What do I need to teach/review with the whole class?

- Is there a small group of students I can pull together to work on a specific topic?

- What individual students need help?

I have also found in interviews with teachers that they are happy for the software to make recommendations to answer these questions, rather than just provide data for teachers to analyze to answer them. It is fairly standard to allow teachers to do item analysis, where they look at the number of students who got each question correct or incorrect (as Savvas Realize does nicely here). However, teachers in focus groups often say they would like to see some headline trends at the top of this such as, “3 areas you might want to reteach to the whole class: x, y, and z” rather than leaving them to do all the analysis themselves. Of course they are likely supplement or change these recommendations based on their own knowledge of students that isn’t available from the platform, but they are still happy to get an assist.

I have also found that just giving teachers alerts based on predicted struggle (e.g., this student is on a path to failing the course) is not sufficient. Not surprisingly, the first question teachers ask is, “what should I do about that?” There are two issues here. First, if this recommendation is based on an algorithm, teachers like to know what that algorithm is basing recommendations on. That’s probably a topic for another day, but underlying this question is, “do I trust the algorithm enough to follow its recommendations?” If they do trust it, the next thing most teachers do is try to figure out what is the cause of the performance that raised the alert. So, they will want to have information about a student’s effort in particular. The data gathered about time, attempts, and steps can all help inform teachers as they try to determine how to intervene.

However, if you’re imagining teachers poring through data, you will probably be disappointed. One district found teachers on average logged into an online dashboard system with assessment results a total of 33 times during the entire school year. Anecdotal evidence as I talk to people across educational technology is that, despite significant efforts being put into design, dashboard usage remains low. So, that’s another challenge for companies aspiring to do work in this area: providing insights to teachers in ways that they will use.

To what degree do insights need to be “engineered” into the learning platform and content vs. extracted from it by smart data analysis?

I have yet to see a platform that has yielded meaningful inferences about student knowledge and skills just through “smart” post-hoc data analysis because without a plan the right experiences won’t be designed and the right data won’t be captured. If you don’t design assessment into the system, you will end up with lots of noise and very weak signal. You need to start by thinking about what knowledge, skills, or attributes you want to measure. Then think about what kinds of evidence would tell you about that skill or attribute.

Far too often we rely on the selection of one option from a choice of four as our evidence. If we were designing our evidence from scratch, that probably isn’t what we would say is the best evidence. Rather, we would probably say we want to see a student create something, troubleshoot an issue, or at least see their approach to solving a problem. After we know what kind of evidence we want, we can think about designing activities that might yield that kind of evidence. That gives us a logical chain from the activity, to the evidence, to the inference about the skill. That isn’t likely to happen by accident.

Can content and platforms be retrofitted to enable this?

Both activity design and data capture can be retrofitted but sometimes retrofitting is a harder task than designing from scratch. I spent a good bit of time working on game-based assessment and was lucky enough to get invited to be part of a team developing a game-based assessment based on SimCity. It turns out that retrofitting SimCity to provide evidence about systems thinking was significantly more difficult, time consuming, and expensive than building many games from scratch.

However, if you are trying to understand behavior on your platform without making inferences about things as complicated as systems thinking, that can definitely be done. It is certainly possible, after a product is built, to build updated versions that capture data that were not being captured initially, such as information about multiple attempts, or time stamps on events. This information on its own is helpful and important in providing contexts for assessment results.

Looking ahead, what key data capture would you encourage any K-12 edtech company to instrument into their platform to anticipate the promise of next-generation K-12 digital assessment?

The first mistake people make is saying they will capture all the data. This puts huge burdens on both school technology systems and back end data storage to capture a lot of data that, in my experience, does not end up being helpful.

Next, I encourage those developing systems to engage in an iterative process through product development. Just as they do with other product features, they should start with hypotheses about what data are important, based on the process of linking activities to evidence to skills described above, and then test those hypotheses during development. They also might collect significantly more data in these research phases to engage in data mining and machine learning activities to uncover unexpected evidence. However, in production, data collection should be pared back to what will provide clear evidence of knowledge and skills.

With both those caveats out of the way, some general advice on what data to capture in K-12 digital assessments:

- Ensure you are able to track individual students through your system over time, including across multiple sessions. You may think you want to develop an anonymous system, but if you’re serious about learning, you need to measure it, and you will need to follow people over time.

- Capture all student text input (if you meet me in person I’ll tell you the story of how someone decided to only capture the first 100 characters of an essay assignment!).

- Store all attempts and ensure they can be ordered (with time stamps, counts, or both).

- Give your items unique item IDs and your multiple choice options unique option IDs, don’t just record a, b, c, d – you may want to randomize those choices and then guess what happens!

- Find ways to capture the start and end times of activities. When does someone start working in your system? Start working on a problem? Finish working on that problem? Leave the site? Remember, think about the questions you will want to ask in your analysis. Many of them will be, “how long did they spend on x?” Make sure you have time stamps that will allow you to know.

If you have more passive learning activities, like watching videos or reading articles, find ways to track when they started and stopped or exited so you can go beyond “well they opened it” to answer what they viewed and for how long.

3. Market constraints and opportunities for realizing the promise of next-generation K-12 digital assessment

What are the biggest barriers preventing teachers from adopting these next-generation K-12 assessment approaches? For schools?

There are two main issues I’ve discussed: using activities that allow for greater application of knowledge and skills in contexts like the real world and use of ongoing data to measure skill mastery. For the first, the biggest limitation is the lack of available digital tools that provide rich activities that yield good assessment data. It turns out these kinds of experiences are expensive and time-consuming to build so there is not much choice out there.

In terms of using ongoing digital data to inform instruction, the first barrier seems to be getting teachers to actually look at the data. Across a number of products that I’ve been involved in during my career data has shown that only a very small percentage (often less than 10%) of teachers access reports at all. If teachers are finding the data are not helpful or not in a format that is useful, I encourage them to let both their district buyers and customer service at the company know. Most companies are looking for feedback. If you are an edtech leader, try to figure out how to get to the “average” teacher when designing reporting – rather than designing for power users. It may be that companies need to figure out how to get information to teachers in other ways, through LMSs for example.

Do exams need to change first, or can teachers and learners enjoy some of the benefits today?

Given the accountability emphasis placed on the end-of-year exams, it definitely makes sense for teachers to try to align their classroom assessments to those exams. However, I also find teachers are eager to get at assessments that they believe help get at higher-order thinking skills like application and analysis. So, it is likely they would be interested in incorporating those into classroom assessments without changes to end-of-year exams, although it may be as a supplement to what they have instead of a replacement.

4. How can next-generation K-12 digital assessments be more equitable?

There’s on-going concern that current assessment practices reinforce our societal inequities. Do you believe the digital strategies you’ve described above would improve this? How?

A huge issue in ensuring equity is that assessment results are so often interpreted as telling us something about the success or the potential of the individual, but they actually reflect different opportunities. We have to be clear that even when we are measuring achievement of recently presented material, there are often systemic reasons that compound over years that make it difficult for some learners to be successful with that material. So, a first issue we have to understand is the extent to which so many of our assessments are measures of opportunity to learn and ensure we are deriving appropriately cautious inferences from them.

It is possible that digital assessment can provide contexts that resonate more with historically under-resourced groups, which would make it more likely that they will be able to successfully demonstrate their newly learned skills. However, this has to be designed in. There is definitely a risk that we replicate biases in the digital world.

This danger of replication can also be true when we think about using data mining and machine learning to infer knowledge or skills. If our training data sets contain biased information, our new assessment models will replicate that. So, new forms of assessment are not a clear answer to our questions about equality and we have to continue to research how to move our assessments in that direction. Equality is a very human problem and I suspect we will not find technology solutions to alleviate it.

5. Common pitfalls to avoid when designing digital assessment

Looking ahead, what pitfalls should edtechs building K-12 digital solutions avoid in assessment and how can they “engineer” for the future you’ve outlined?

A common failure of early edtech startups is to ignore the need for expertise in learning and assessment. There is a tendency to think that businesses that have been working in this space for a while are entrenched in the system and since the goal of many startups is to disrupt the system, there is no need for their expertise. I would recommend the recent book by Justin Reich called Failure to Disrupt that lays out some of the reasons that recent history is littered with edtech companies that ran headlong into the education system and failed to disrupt. Without understanding the current education landscape, what has been tried before, which constraints are movable and which are not, companies will continue to fail. edtech companies need to understand schools as a system and should ally themselves with people who have spent time working in and with that system.

Specifically with regard to assessment, there are decades of work developing the backend statistical machinery. I have at least twice in my experience run into data scientists who are basically reinventing Item Response Theory (a paradigm for scoring assessments used in most major testing programs) from scratch because they realized the need to estimate item difficulty and learner ability at the same time. In addition, traditional assessment work has a well-developed understanding of error in estimates, which is essential in measuring learning and achievement because of course we can never get precise measurements of what someone knows just by observing them answer a few questions. These are just two small, specific examples, but the general idea is that edtech companies should seek out assessment expertise because they often don’t know what they don’t know.

6. Favorite resources on digital assessment design

What practical research resources would you recommend to edtech leaders for insights into how to engineer their content and platforms for these future opportunities in digital assessment?

Before leaders start to try to engineer their content and platforms, they would do well to dive deeper into understanding how technology and the science of assessment relate. This piece by Val Shute at Florida State University and her colleagues is an excellent primer. It is long and dense but well worth it!

If you’re new to assessment design, the U.S. Department of Education has an excellent Assessment Design Toolkit.

If you want to write traditional assessment questions, there is much existing guidance about how to do so. Given how much we still rely on these even in our new systems, it is worth reviewing the TIMSS 2019 “Item Writing Guidelines” (begin on page 12) and Dr. Nathan A. Thompson’s Item Writing and Review Guide.

I wish there was simple guidance I could link to on how to develop assessments using the stream data from digital learning environments, but this work is still in early days, so unfortunately best practices and guidance for novices are still in development.

7. What question do you have for me?

Given how many ed tech leaders you meet, how much do they talk about assessment?

That’s a great question, Kristen. I get asked many questions that relate to assessment, such as: what are better ways to drive student engagement, encourage teachers to use more formative testing, or transform data into actionable insights? But, not many about assessment design itself. And, I come across relatively few edtechs pushing the boundary of assessment design. So, I see great promise for innovation in next-generation K-12 digital assessment along the lines you’ve described.

Takeaways

Kristen has shared a wealth of insights into the promise and practicalities of next-generation K-12 digital assessment. Coupled with my own experiences critiquing edtech products, here are some key takeaways for any edtech company building K-12 school products:

- Your opportunity. Testing sucks up a lot of time for teachers and learners. So, well-designed activities that include formative assessments can reduce the need for testing and liberate teachers’ teaching time and learners’ learning time.

- Understand the ecosystem, and help drive change. K-12 is particularly complex because of precedents and constraints. Make sure you understand these so you focus your innovation on what’s movable. As Kristen flags, even with end-of-year exams fixed, many teachers are hungry for smarter ways to measure formative progress and higher-order thinking skills (like application and analysis).

- Get talent early on. Effective and empathetic assessment is fundamental to successful K-12 edtech, so hire an assessment expert early on in your business. An expert with deep experience of teaching practice and commercial considerations will add value well beyond just assessment.

- Don’t reinvent the wheel. There are decades of research into effective assessment design. Make sure your teams (and assessment talent) are familiar with this so you don’t burn through precious time and money reinventing the wheel.

- Start at the end. Stating what may seem obvious but is often ignored, start with what knowledge, skills, or attributes you want your edtech to help teach. Then design activities (and data capture) to build the most robust set of evidence to try to measure these.

- Iterate on data capture. Trying to capture all data (e.g. clickstream) isn’t a strategy, let alone a good one—it’s expensive to maintain and—trust me—you’ll miss engineering critical data into your activities and platform. And, retrofitting content and platforms later is often prohibitively expensive. Instead, use the plan of what you want to measure (above) to iteratively test and narrow down to the best set of data and ensure you capture this. I have nearly identical recommendations to Kristen’s excellent list of critical data to capture. Two of the most common mistakes I come across are:

a. Storing only a student’s last submission—instead, store every submission since each gives insight into the student’s journey.

b. Storing only time stamps of a student navigating the product—instead, capture their time between answer submissions (and resubmissions) within activities and when they open, pause, and exit video (or other passive media) since that will give you a wealth of critical insights (into them, your content, and UX). - Stay humble and empathetic. Remember that assessments help us to infer knowledge, skills, or other attributes, but that these inferences could be incorrect. So, ensure you design your products to always give teachers and learners choice.

- Help teachers interpret and action data. Make sure assessments and results are transparent so teachers can draw their own conclusions. But, assume most are busy and will welcome products that provide actionable insights on who, when, and how to help. Test and improve these to satisfy (and reach a bit beyond) your core target users—but don’t be hypnotized by the needs of power users. (See also my guidelines on How to design actionable edtech dashboards and Dashboard design examples.)

- Make equity a strategic mission. Many traditional assessments have biases built in that prejudice some learners and their contexts. Next-generation assessments that use AI carry similar risks depending on what they’re trained with. Make it your mission to build next-generation assessments that are equitable by design. (See also Takeaways for Leaders in my interviews with Prof. Liz Thomas and Dr. David Porcaro and upcoming guidelines from New America and SHEEO.)

Need help?

If you want an experienced critique of your product, data capture, and strategy, and practical recommendations for how to improve all three to accelerate your growth, please contact us today with the form below—we’d love to learn more about your business, aspirations, and challenges.